Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission for purchases made through the links. I only recommend products I have personally used or recently purchased but not yet used.

People want to do right by others.

One of the biggest concerns many people have when traveling to a new place is safety. We want to know that where we’re going will not result in harm being done to us by others or by the environment we enter. These are legitimate concerns that should be taken seriously, especially if you live in a body that is more vulnerable given cultural norms and expectations.

All that being said, I’m often surprised by the kindness of strangers when traveling, and India is no exception. I’ve encountered some challenging situations in India, but even in those scenarios, there was a clear exit path that left me shaken, but not deeply scared or harmed. And these were just a handful of experiences among the thousands of interactions I’ve had with people in the country.

During my time in India, I have been more likely to meet lifelong friends than encounter “bad people.” On this most recent trip, this consistent phenomenon prompts me to reflect on the current global and US political climate. The vitriol that serves as political discourse can turn us deeply cynical to the fact that most people would rather do good than harm, and that what so often tips the scale in how people act is the freedom of choice they have to do the right thing.

Me and friends in Jodhpur.

If, for some reason, I were ever stranded in central or western Rajasthan, I know a dozen households that would shelter and feed me indefinitely without hesitation. Count another dozen that would do so simply because I am personally known to that first dozen. I cannot tell you how rich that makes me feel.

India has become a second home for me over the past 15 years. I was reminded of the depth of those feelings after returning to the country this past May to rekindle professional and personal relationships that had last been explored twelve years ago. Homes are shaped by the people of a place, and the love and care I experience in India can only come from a nation of people deeply invested in doing right by others.

Inequality is soul-destroying.

For everyone, especially those on the more affluent side of life.

Having nice things and having people do work for you is undeniably enjoyable, but the labor that goes into providing those goods and services is not without cost. Any labor that gives you something that you did not do yourself is done by someone else. Our economy is supposed to account for that labor via a network of exchanges, and a fair and just economy is built on a network of reasonable exchange value for labor. Of course, most human societies of the last dozen millennia are obsessed with cheating a fair exchange economy for material gain. Thus, we find ourselves in an entrenched system of inequality.

I abhor injustice. Ever since I was a child, people who knowingly did wrong for personal gain enraged me. I got into fights about it all the time. Since becoming an adult, I’ve confined my anger at injustice to interpersonal interactions, attempting to correct wrongs done to myself and others in my immediate vicinity. That being said, I’m a hypocrite and enjoy countless benefits of exploitation by living in the U.S., and by choice.

The inequality you can observe in India is stark and immediate. Much of Indian society was built on a caste system that is still relevant today, though things are slowly changing. There are entire castes of people tasked with removing and processing dead bodies (human and non-human) and are not allowed to be touched or interacted with other castes.

Men loading livestock carcasses for processing

Just as conspicuous to me are the people responsible for serving tea, guarding property, cleaning up, cooking, and those working in construction. No one who can afford to pay someone to do those tasks does so. In households, the majority of cooking and cleaning is typically done by women and children. At the household level, particularly across genders, there is a deep inequality of movement and interaction for most women. During my dissertation, it was rare for me to interview a woman in villages, as the men were the spokespeople of a given household.

Now, I think it’s important to mention that my observations in Indian society are by no means unique, more restrictive, or inherently worse than U.S. society. The U.S. still maintains a strict and violently enforced caste system. We still have debilitating gender inequality, and most in our society aspire to achieve a level of wealth and luxury that allows us to pay someone to do the things we’d rather not be bothered with.

In both cases, and whenever I observe these types of inequalities, I feel bad that my horizons are less limited in many ways than others. As I wrote a few posts back, flying business class was bittersweet because not everyone can travel in such comfort. I feel the same sense of cosmic unfairness when I see an exhausted Black person my age working behind a fast-food counter, as I do when I take the cup of chai from the dark-skinned Megwal widow who is kind enough to welcome me into her home. Perhaps neither would want the luxuries and conveniences I have and appreciate, but I know that, through no fault of their own, they have no or very limited access to the same.

For those who experience the benefits of systemic inequality, one of the most significant risks—and indeed a key element in maintaining inequality—is the beneficiaries’ belief in their inherent right to exploit others. I often observe this in the way people in the U.S. and India regard the humanity of those who serve them. I saw it in myself until friends and colleagues in graduate school patiently disabused me of that pattern of thinking through their research in African American studies.

Elon Musk doesn’t demand access to the personal data of an entire country unless he feels entitled and superior. Donald Trump doesn’t claim he could murder someone in broad daylight and not lose any votes unless he feels entitled and superior (he’s also right about that). Joe Rogan seldom hosts women of color on his popular podcast, and he hasn’t changed this pattern because he believes what women of color have to say is simply less important and interesting. And we all suffer from these delusions born out of inequality.

Good food is medicine.

I don’t speak Hindi, but I do speak good food. I don’t know how to say ‘I love you’ in Marwadi, but I do know how to show my appreciation for your hospitality with a smile and a good posture. I can’t tell you how the countless delicious foods I’ve eaten in India were made, but I can tell you how to show my gratitude for the care I’ve received over the years.

Eating a delicious Rajasthani dinner at a friend’s home (standing) in Bikaner, Rajasthan.

Every time I’ve eaten food in someone’s home in India, I’ve been closely watched. The first couple of times, I didn’t notice, but afterwards, I became very aware that a lot was riding on my reactions to the food and how much of it I ate. For most people I’ve met, my primary and sometimes only interaction with them is centered around the food they serve me. In villages where married women keep their faces covered by veils, I can feel their eyes closely watching my reactions. I’ve learned to observe the tension and anxiety melt away in postures as I nod, smile, and ask for seconds —a clear indication of my enjoyment and an endorsement of the job they’ve done as hosts.

An impromptu local meal prepared by the family that looked after me during my dissertation.

You simply cannot replicate the level of deep satisfaction humans give each other through good food lovingly and respectfully prepared and taken. These moments are some of my favorite in life, and one of the joys of my travels to India over the years. I love to connect with people in this way, not least because I’m being nourished, but I also try to return some of that nourishment by being grateful and curious about the food. I ask and attempt to pronounce the names of the dishes and ingredients correctly. I try to remember the names of dishes I’ve had and delight in the smiles of surprise when folks who don’t expect it, here, beloved dishes pronounced in their language by a foreigner.

Vegetarian Thali meal at a restaurant in Jaipur, Rajasthan.

Eating Indian food in someone’s home is an experience I treasure beyond words. It brings me back, heals my anxieties, and I leave better off than when I arrived. I hope folks feel the same.

The Wild Kitchen and India

My experiences in this country are almost exclusively limited to Rajasthan. I’ve only ever experienced Delhi and Mumbai outside of the largest state in the country. Somewhat ironically, given the author of this newsletter, hunting wildlife is extremely restricted across the country due to cultural and environmental reasons. I have a limited understanding of wild foods in India, aside from a few species that are foraged by local people in rural areas. That should change.

A local woman walking on a village road encounters a blackbuck antelope—photo taken during my dissertation research.

Where the intersection of The Wild Kitchen and my experiences in India intersect is around the dinner table. The same types of connection that come from preparing and sharing wild food in the U.S., I’ve found at kitchen tables in India.

I rarely understand the words in conversations that happen around me when eating food in Rajasthan, but I do understand the nature of said conversations.

My friend and mentor (foreground) engaged in a political discussion with his uncle (background).

The Wild Kitchen wouldn’t exist without my time in India, because it’s where I began to understand the universality of food as a language and a connection. Food is universal, and the more stories a meal contains, the richer the experience that can be shared.

CONSIDER THIS

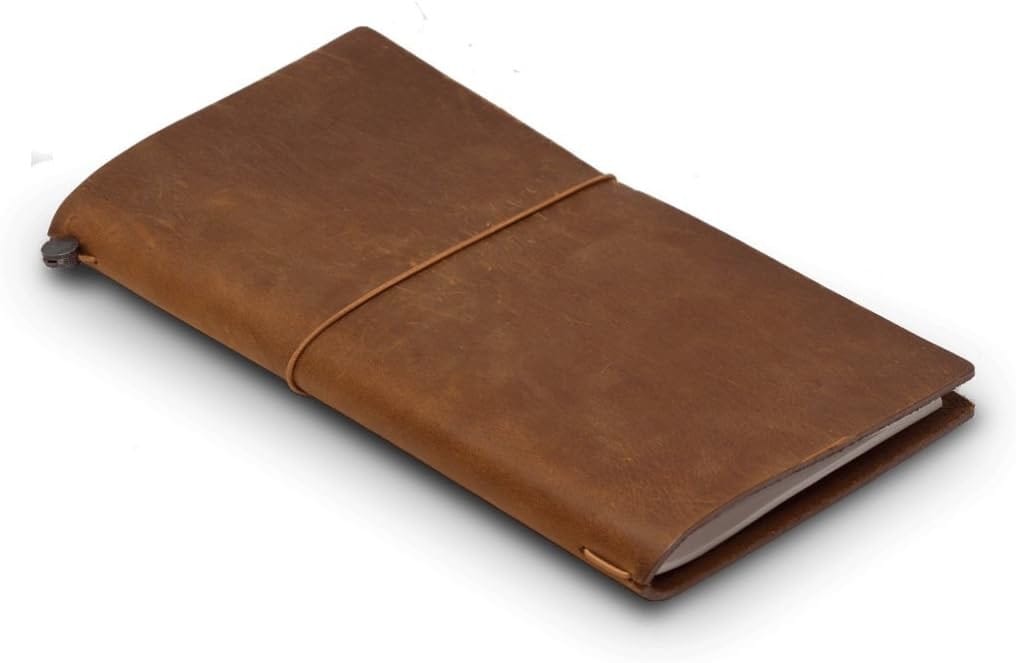

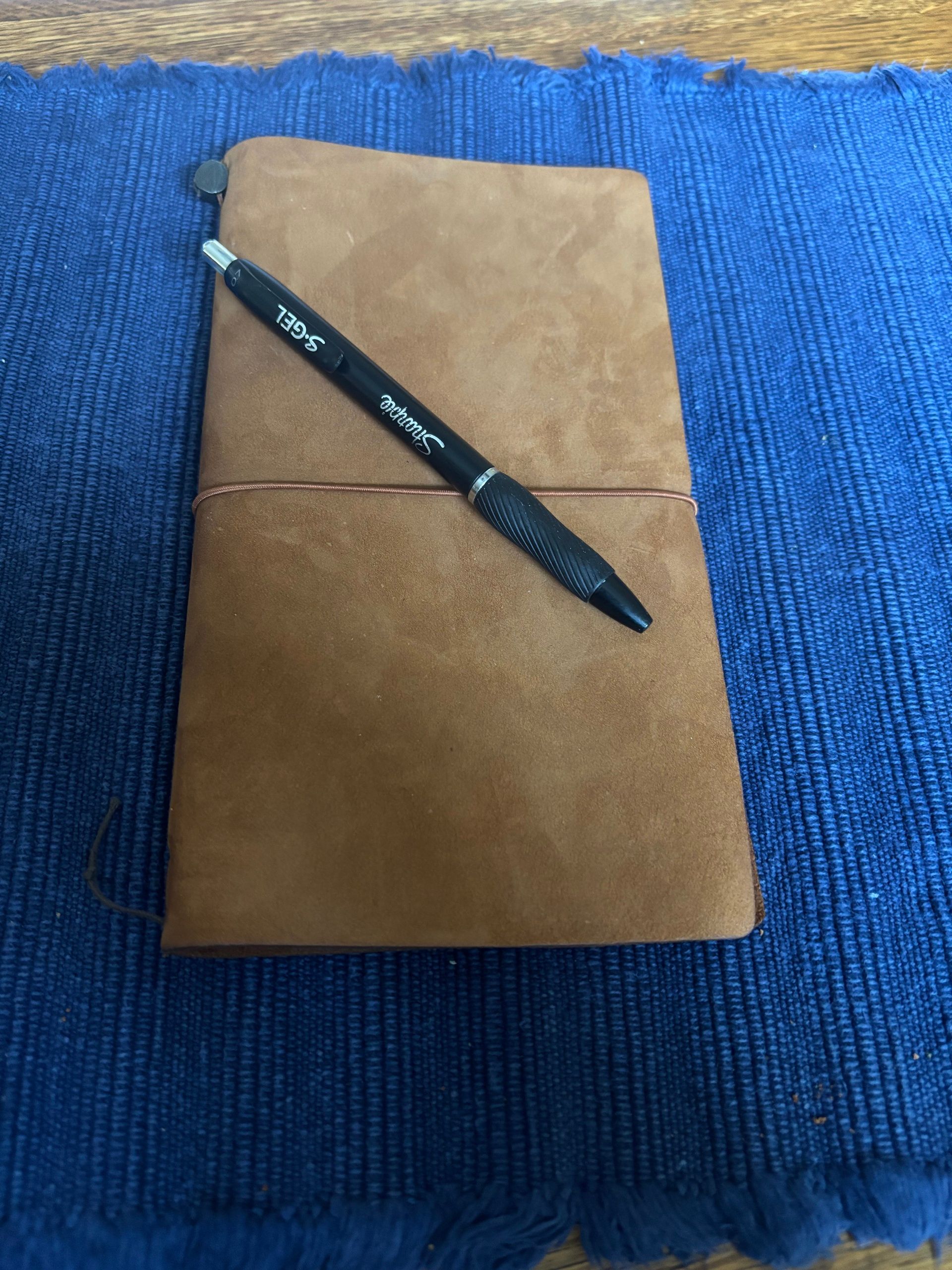

Maurice Moves on YouTube remains one of my favorite creators, and I recently came across his video on using a specific brand of notebook for virtually everything creative he does. So, I decided to buy one.

The Traveler’s Notebook is definitely a notebook for notebook nerds, but it’s also a fantastic product. What stands out to me is the paper that they use, which is easily the best quality paper I’ve ever used. The most surprising feature of this absolutely buttery smooth paper is the fact that it doesn’t let ink smudge. Lots of times when writing on other types of paper, I’ve written something down, run my hand across the page, and end up with ink streaks and ink on my hand. Not at all the case with Traveler’s notebooks and reason enough, in my opinion, to consider using this notebook.

You can customize and accessorize Travelers notebooks up, down, and sideways, which is a fun feature, I suppose, but I don’t plan to get into those options quite yet. This notebook dovetails with my middle-aged pursuit of high-quality products that last and seem to be well thought out in their engineering and manufacturing. I also love that there is a store in the Tokyo airport and will visit if/when I’m ever traveling through or visiting Japan.

The enjoyment I get from this notebook is helping me build a daily habit of journaling that I’ve been unable to stick to using a digital platform. Traveler’s notebooks also make great gifts, so check them out!

NEW ON YOUTUBE!

Despite 47’s recent bill, electric vehicles are still the wave of the future, and I’ve been opportunistically testing EV trucks to see if any of them could be something I’d be interested in purchasing down the road.

In the latest video on my channel, I give the Silverado EV another try during my trip to North Carolina for a pig harvest event in December. This is the second time I’ve tested this vehicle in a rental situation, and the results are, to say the least, interesting.