Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission for purchases made through the links. I only recommend products I have personally used or recently purchased but not yet used.

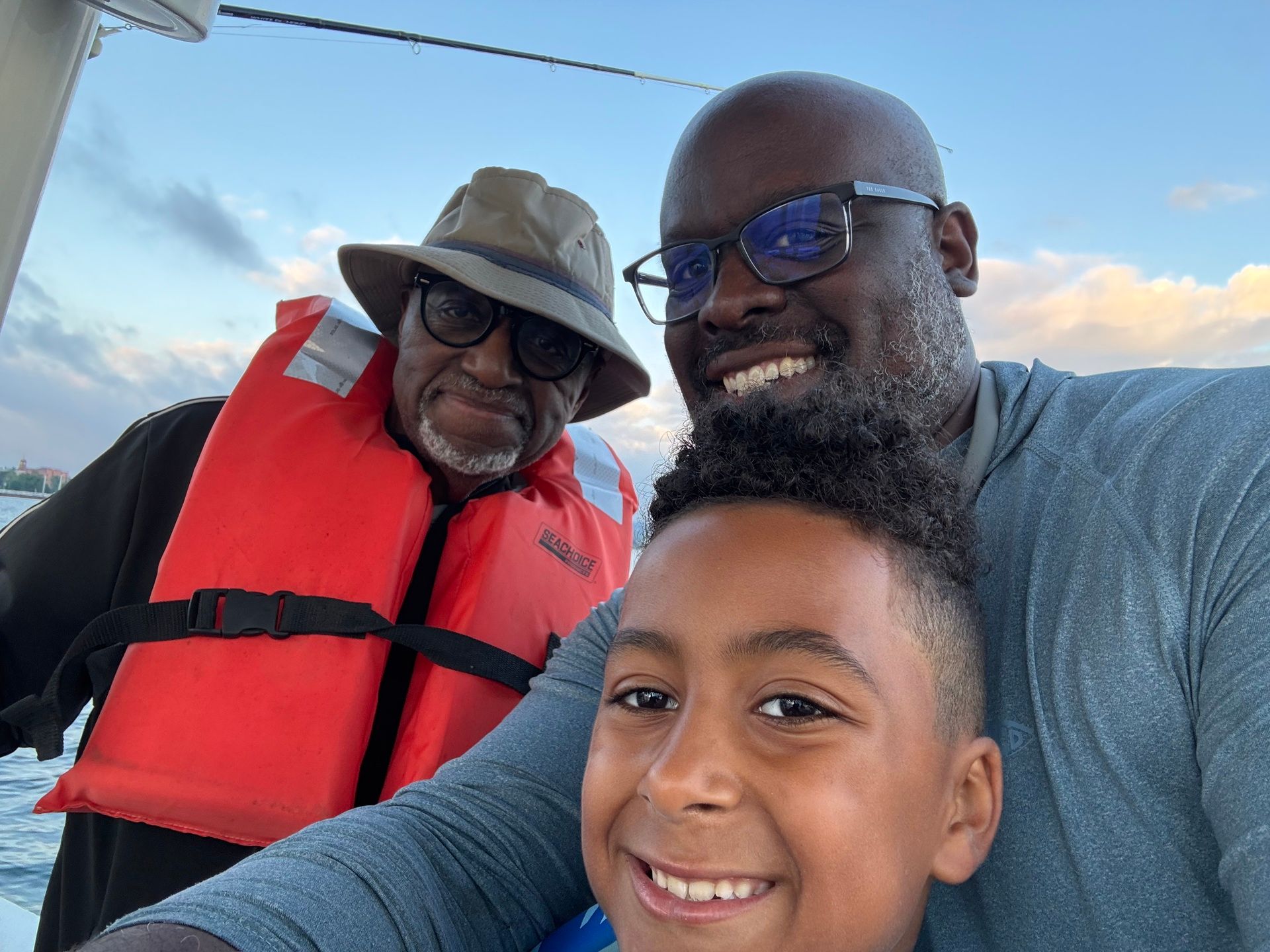

Three generations on the same boat.

One of the things I looked forward to most when I got hired as a professor at a Michigan university was the access to world-class fisheries. Four out of the five Great Lakes are accessible from Michigan, and the species available to anglers is among the best in the world. I was geeked to move to the region and take advantage of the bounty.

My dad was geeked too, and two years ago, we had the best fishing adventure the two of us had ever had. You might know that story, but in case you don’t, you can watch it here:

That was an incredible trip, and in many ways, it won’t ever be eclipsed. This latest Lake Michigan fishing trip, however, was equally as memorable and special. The fish we caught were bigger, and the crew that went was uniquely meaningful.

I didn’t think our 8-year-old son wanted to go, but a week before the trip, he changed his mind and got really excited about the idea of catching fish with his dad and Pop Pop (my dad). A few years ago, on Father’s Day, our family had an accident that almost turned into a tragedy. We rented kayaks on a lake that were not rated for a parent and child, and ended up sinking the vessels in the middle of the lake. Fortunately, we were rescued by kind boaters and also managed to save the kayaks. I almost decided not to wear my life jacket, and had I not, there’s no way I would have been able to tread water long enough to get rescued.

Our son was in my kayak and had a lasting phobia of deep water and vessels that might tip over. He’d been working through that trauma and made lots of progress, but I was convinced he was not ready to be out in the middle of Traverse Bay in a relatively small boat, despite his love of fishing.

I was skeptical until I saw his face after he stepped onto the boat at 5:30 AM (this is the guy we went with for our charter; highly recommend him) on that rainy Saturday. There was no hint of nervousness on his face or in his body. Just pure excitement and anticipation. He matched the expression of the three of us, and I could now relax and take in what ended up being a truly special day.

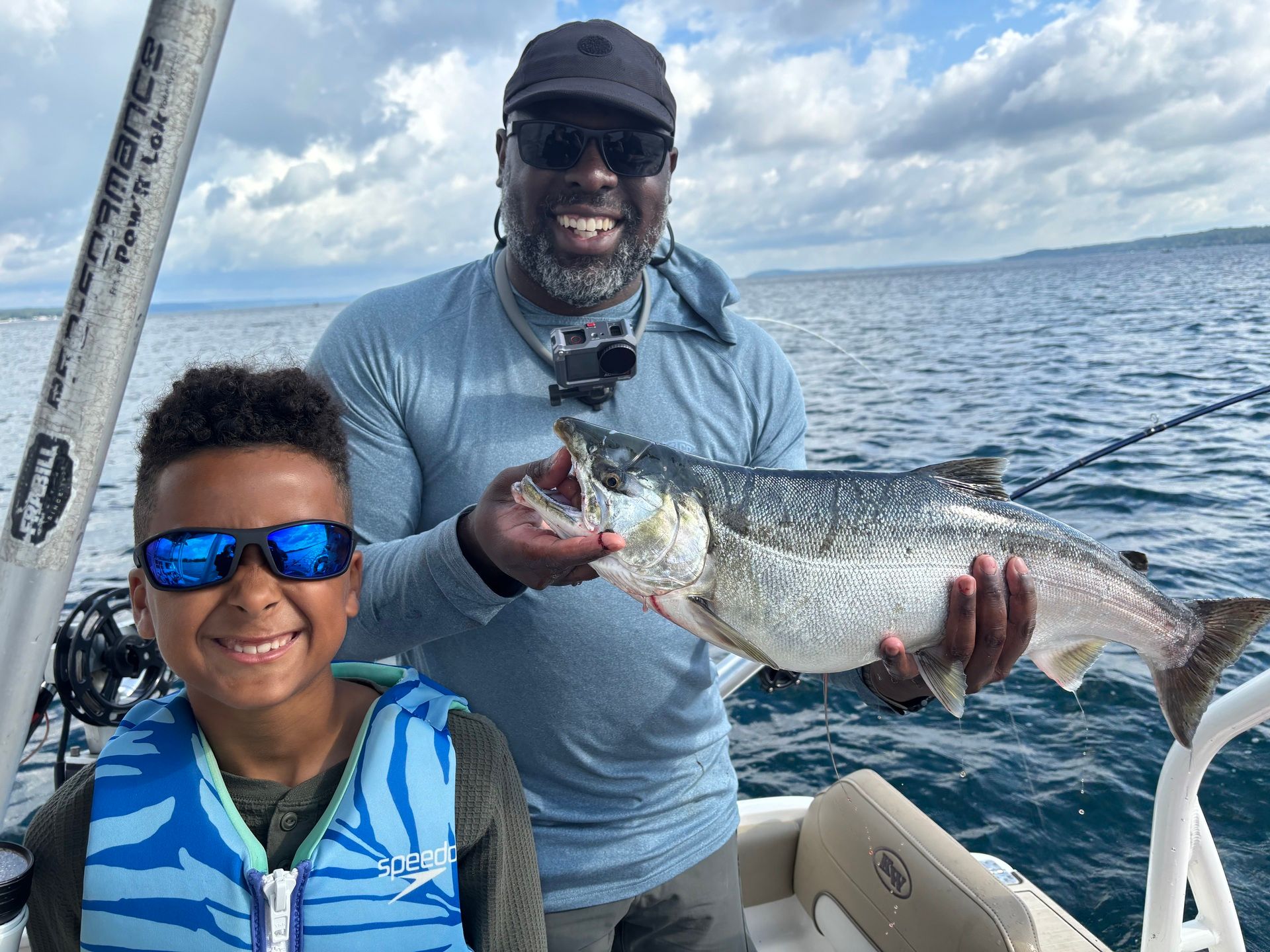

My son and I with a 9lb coho salmon.

“Three generations of Halls! Aww man, this is so special, son!”

“Yeah, Pop, it is.”

Three generations of Hall’s fishing in Traverse Bay, MI

The work of wild food.

As much as I love harvesting wild food, I love processing it more. Or maybe equally as much. The thing about processing your own food is that shit is work!

But it’s joyful work. I love reliving the story of each relative harvested. When I’m filleting a fish, I can recall the exact details of how our paths crossed. I know the sweat that went into winning the fight for their lives, how they fought hard to stay alive, and how almost half of the fish we hooked got away. These fish fought and died well, never giving up, which is a call for me to honor their lives, their fight, their wisdom, and their sacrifice.

Six beautiful wild-caught salmon!

The first attempt to scale, fillet, and process these fish was a disaster. My knives were dull, the slime these fish produced when scaled was prodigious, and my setup was just ill-equipped. I regretted not filleting and processing these fish at the dock the day before, and thankfully, I took a needed break to run my dad to the airport with fillets from the giant you saw at the start of this article.

On the way back from the airport, I reminded myself that filleting the fish the day before wouldn’t have worked. It would have taken several hours and gotten us back super late (not great for an almost 8-year-old’s sleep routine), and I didn’t come prepared to seal the fillets so that they aged properly.

Gutted salmon ready for ice and a 4-hour drive home!

Rather than make excuses and wishes, I decided to problem-solve. I went to Home Depot and bought a squeegee, a pack of microfiber towels, and a small handheld brush. The squeegee to remove standing water and fish bits from my work area, the towels to clean my hands, knives, and tools, and the brush to scrub off the copious amounts of slime these fish exuded. I flipped the orientation of my workstation so water flowed off the table and away from me instead of towards where I was standing, and I was in business.

Filleting the remaining three fish took astonishingly less time than I thought it would, and before about an hour had passed, I had everything broken down into manageable parts and sizes. I was still exhausted, but the meal of fish collars and bellies we ate that evening was significantly better because I had figured out how to manage the task and had fortunately built a collection of tools to make fish mongering run more smoothly.

Here’s my process:

1) Land fish on the boat.

2) Ike jime fish immediately.

3) Gut fish at the dock, making sure to clean out all the blood in the body cavity. Keep roe (fish eggs) and livers.

4) Pack fish in ice.

5) Scale and de-slime fish at home with a scaler and brush.

6) Fillet fish.

7) Remove pin bones with this tool and this tool only (serious, it’s the best bone removal tool I’ve ever used).

8). Separate bellies from larger fillet. This is why:

9) Remove collars and keep with bellies.

10) Remove heads and store with the remaining skeleton.

Done!

Catching your own fish and/or buying whole fish is such a more rewarding experience than buying fillets at the store. Whole fish are cheaper, and you’re able to get more from the animal relative by acquiring their entire bodies intact.

Yes it’s work, but I’ve now got 10lbs of premium salmon fillets, 13 quarts of fish stock (from the heads and skeletons) that I can use for all sorts of things (ramen, seafood stew, risotto, etc.), an entire quart of ikura, enough steelhead bait (the rest of the roe frozen) for multiple fishing trips, and three meals for four from the collars and bellies alone!

Salmon collars and bellies with rice and charred broccoli.

That’s good work!

The Wild Kitchen and Michigan salmon.

Salmon are non-native fish relatives of the Great Lakes. They were introduced in the mid-twentieth century because native fish populations were irreparably overfished. I’m glad salmon are here, but the story of how they came to be here is a tragic and familiar one.

I’m reminded of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s concept of being a good invasive relative in her book Braiding Sweetgrass. Plantain, the green leafy plant, not the delicious banana cousin, was, to her, an example of an invasive species introduced to Turtle Island (North America) that had sought a place in the local ecology without domination or destruction.

I like to think salmon are doing just that, and because they are here, I’m attempting to follow their lead in how I relate to them and the space they now occupy.

The ikura I made turned out delicious, but then I was reminded by a friend that PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” are highly concentrated in the eggs and fatty tissues of fish. Devastating.

Leftover salmon bellies, rice, and homemade ikura (marinated salmon roe)

One of the things I hope my son took away from this trip is part of the awe and respect I have for salmon. It’s hard to describe their power and beauty without holding one in your hands. They can be so abundant and gigantic that it becomes overwhelming to think about how fortunate we are to weave our lives together with theirs. No wonder many Native peoples consider themselves Salmon People, when these fish can literally sustain other communities just on their own.

We need the stories of close personal relations to teach us to care about these relatives more than our current society makes convenient for us. I love the taste of ikura, the tedious yet delicate process of making it, and the way it enhances the enjoyment of life. I want my son and others to experience that story, to weave their own perceptions and observations into that collective story, but I won’t feed him ikura because of the risk it poses.

That caution is part of the story, though. It’s a reminder of something we’ve lost because of systems we’ve built as a human society that deprive us and literally poison future enjoyment. You don’t poison the water salmon live in if you love ikura, or fillets, or collars, or to see these magnificent relatives swim and exist.

Fighting the generational destruction of Anti-Indigenous Civilizations requires more than rhetoric. You literally have to taste it!